It is a common belief that project outcomes contain a degree of uniqueness. They may be highly unique, such as in space exploration projects, or only very slightly unique, such as in the construction of a number of identical buildings in an office park, where uniqueness may reside simply in a set of user requirements or geotechnical properties of the site.

By contrast, it is also widely accepted that project management processes are repetitive. In other words, the management effort follows the same path, whether we are managing a feasibility study phase or a construction phase in the project life cycle.

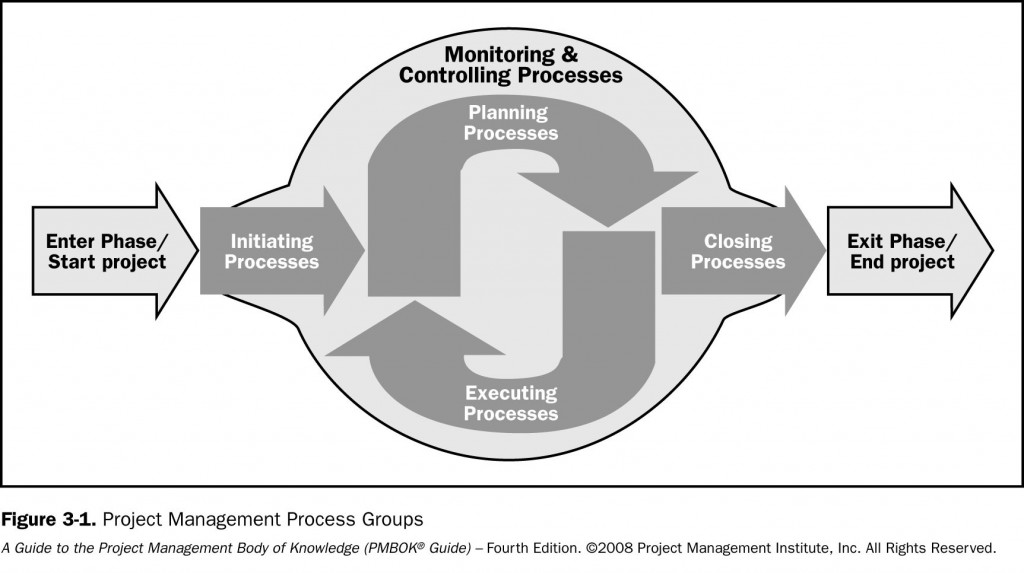

Early editions of PMI®’s Project Management Body of Knowledge or PMBoK® simply stated that the project management process groups of Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing, repeated themselves in each project phase. Process groups mind you, and not necessarily every individual process. For instance, if a phase or a whole project for that matter is performed in-house we may not need to perform any procurement processes.

The principle underlying this concept is that of progressive elaboration: the constantly increasing level of understanding and definition of the product of the project requires the repetition of the management processes through the various phases.

Reasonable as it may have seemed at the time, this concept is probably responsible for most of PMBoK®’s woes:

- Firstly it has led to huge and unabated confusion, and

- Secondly, it has never been really tenable.[1]

Later PMBoK® editions, and particularly PMBoK® 5, have tried to soften the rigidity of the concept by discussing different project approaches and life cycle concepts, but nonetheless they admit that the idea of iterative processes is still there.

The consequences of these woes are hard to underestimate: A few years ago, SUKAD did a survey amongst PMP®, asking them to name the life cycle phases of projects that they were working on. More than 50% listed the process groups, with some people leaving out the M&C group. If half of the certified PMP®’s out there are unsure, what about the less initiated?

Factors that contribute to this confusion may include:

- Unfamiliarity of project managers with industry lifecycle models. It is a fact that people who have been exposed to those have no problem separating phases from processes.

- Terminology, where process group names may be very similar – if not exactly the same – as some of the phase names.

- Inconsistent naming of processes in PMBoK®: ‘Develop Project Charter’ and ‘Develop Project Management Plan’ hint at a once-off nature, while ‘Close Project or Phase’ is more in line with the repetition concept.

- The ambiguity of the term ‘Develop’ in itself: In the very first phase of a project it would probably mean ‘create’, while in subsequent phases it would have to mean ‘expand’ as the original version of the Charter/Project Management Plan already exists.

- If the above is the case, are there no phase initiating documents or phase management plans?

Fortunately many mature[2] companies have a trademark in-house method, and most of those enforce the use of it for their projects. Those methods are easily compatible with PMBoK®, as PMBoK® is a universal framework, and not a prescriptive method[3].

But in companies without a method, project professionals and executives are often referred to PMBoK® as their only guideline, and therein lays a problem, for the above reason. With a major focus on processes it is easy to overlook the design of a lifespan for the project at hand, and without this the project is already at a disadvantage, as it will be extremely difficult to yield a successful outcome.[4]

There also seems to be a widespread failure to distinguish between project planning and product definition. While they can overlap in time, the former is performed by the PM team, while the latter is performed by the technical staff of the project team. Yet the terms ‘planning’, definition’ and ‘design’ are often used interchangeably.

So it seems the overwhelming success of PMBoK® is also its downfall: it is so generic that it applies everywhere (well, to ‘most projects most of the time’) and it has its place, but it falls horribly short as a method.

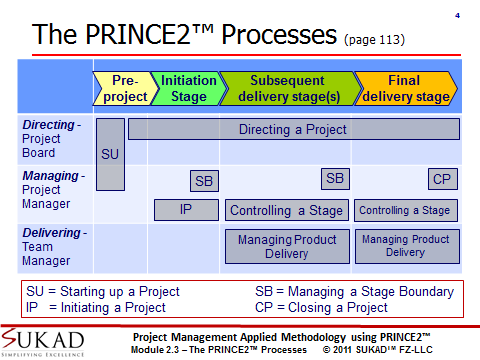

If we compare for example with a method like PRINCE2®, we notice that PRINCE2® has 7 processes, comprising 40 Activities, similar to the 5 process groups and 47 processes of PMBoK®, and 7 themes, similar to the 10 knowledge areas of PMBoK®. In PRINCE2® the project lifecycle is designed as part of the tailoring effort and is done during the Initiating a Project Process.

However, only 3 of the 7 processes are then repeated in each delivery stage. These are:

- Controlling a Stage

- Managing Product Delivery

- Managing a Stage Boundary

The remaining processes are:

- Starting up a project

- Directing a project

- Initiating a project

- Closing a project

These are only performed once on a project. There is little room for misinterpretation.

So, while the idea of progressive elaboration of a project is a noble one, its direct link with the concept of repeating process groups has become nothing more but a romantic notion, and in our opinion, very much out of place, except in a very generic theory of project management.

Isn’t it time PMI® re-think the positioning of its core product?